A Story of Wonderment…

The first artwork I ever saw was a print my mother had brought from Cape Dorset in the Arctic of an Inuit mother and her two children. Its basic form was cartoon-like and it hung in a corner of our kitchen. Another lingering image was that of a boy with a satchel sitting atop some steps to his home with a sign tacked on the door saying, “please use another door” and it affected me in much the same way as had the bedtime story of the Little Match Girl. It distracted me as I learned my scales.

Every summer my friends and I would spend days hanging around Saint Coleman’s College during the installation of the Claremorris Open Exhibition, we ran amuck exploring, climbing, jumping in piles of bubble-wrap and competing for the loudest snaps. It was there that I got my first flavour of the art world, by then the COE was in its eighth year. Every year the school gym was besieged by artists, and artworks adorned the walls, stacked high and wide with little regard for visual cohesion. As years rolled by the annual exhibition became an exciting event and my friends and I got roped in, running errands. It was always a mad rush to the finish and high drama at times with artists storming out on finding their paintings hung up in the rafters, or a complaint from concerned visitors about nudity in the artworks on show.

It was there that I got my first flavour of the art world, by then the COE was in its eighth year. Every year the school gym was besieged by artists, and artworks adorned the walls, stacked high and wide with little regard for visual cohesion.

It was exciting to see the works being hauled into the place, out of cars and lorries, covered in plastic and blankets and then unveiled and left against the wall of the gym; dozens of paintings left there without explanation. In those days visual art in Ireland comprised painting, sculpture, print, drawing and some photography. We always set about trying to decode them, using their titles as clues, trying to be the fastest at figuring out what they were about and guffawing if we couldn’t. We’d stand there critiquing and absorbing every image, picking out details that had gone unnoticed, asking annoying questions of adults who were busy getting the show on the road.

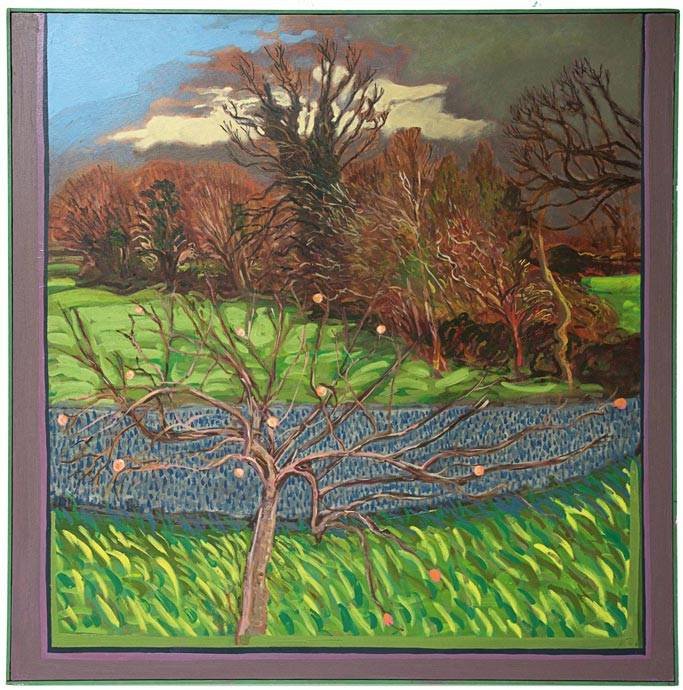

One summer evening during the Galway Arts Festival I was dragged along to an opening where I couldn’t help staring at artist Jay Murphy, elegantly regaled like Cleopatra. When we visited her house afterwards her bearded husband Brian Bourke frightened me but then he put their cockatoo on his head, just to entertain my sister and I, and next puppets came out of nowhere and before we knew it we were watching a full blown puppet show. Brian boasted about a rabbit he’d caught that day but mercifully Jay had already made pizza and after that we wandered out to a studio. That was a new one on me, studio. It was just a shed really; outside it was no different to the sheds where my father tested cattle. But inside was a blaze of huge hot paintings and chucks of wood he’d chiseled into women’s heads. My mother was delighted loading up the car and then we drove the pitch black meandering road to Claremorris.

Around that time there were adult rumblings at home and moves afoot, change was in the air, talk of a new house beside a river, artists coming to visit, staying the night with kids my own age; Michael Farrell barging into the dining room one day; unfurling an enormous canvas which he’d brought all the way from France, the F-word trundling with gusto as he was telling my mother how great the painting was. Edward Delaney arriving with a huge iron spike, that he’d taken from the high wall of George Moore’s Estate in Carnacun, and which my mother flung at the back of the garden as soon as he’d left. That was the first time I had heard mention of George Moore.

It was there that I got my first flavour of the art world, by then the COE was in its eighth year. Every year the school gym was besieged by artists, and artworks adorned the walls, stacked high and wide with little regard for visual cohesion.

In 1989 my mother, Patricia Noone founded the George Moore Society and that’s when the real fascination began. The Society would roll out the George Moore Extravaganza, an ambitious program of events to honour the writings of George Moore, of Moore Hall which was located near Claremorris. He was a 19th Century writer ahead of his time, a feminist, writing about transgender, a big influence on James Joyce and for years he seemed another member of my family.

During the month of July our house had a revolving door of literati, academics, artists, musicians, composers, poets, politicians, RTE personalities. We would be moved out of our bedrooms to accommodate them as the Society did not have the funds for accommodation. Writers travelled from all around Europe, and as far afield as Japan and California all celebrating George and the Moores of Moore Hall. Seamus Heaney read to a packed Town Hall. Paul Durcan, Derek Mahon, Tom Kilroy, Anne Haverty, Anthony Cronin, Benedict Kiely, Anthony Coleman, Robert Welch, Brian Moore all came and read and entertained the people of Claremorris and beyond. With their various partners and offspring they’d stay in our house, invariably carousing into the wee hours and expounding literary theories and claptrap over fries the next morning, egos shadow boxing for hours into the afternoon. There were jazz bands on the lawn at Moore Hall, Race Parties in Ballinrobe, poetry readings, plays, recitals and exhibitions in every corner of the town and county.

I was at least ten years old before being entrusted to serve wine at exhibition openings during the festival. Supervalu sponsored crates of it and my friends and I would carry silver trays with fierce concentration as if competing in the “egg-and-spoon”, and all the while people came and went from throughout Connaught; artists, writers, musicians, locals all talking about art, all gossiping, all guzzling – drink-driving being of little concern in those days. A politician would walk in wearing a necklace and people would hush as he’d talk about regional tourism and the exhibition would open. My mother tried to encourage sales for the Society, saying how much nicer it was to look at art on your walls than zeros in your bank account and someone said, “not when there’s only one zero”. Viewers marvelled at the Tony O’Malley paintings and the price of them: at £200, a week’s wages in those days; “Sure anyone could do that”, the most common refrain during gallery invigilation.

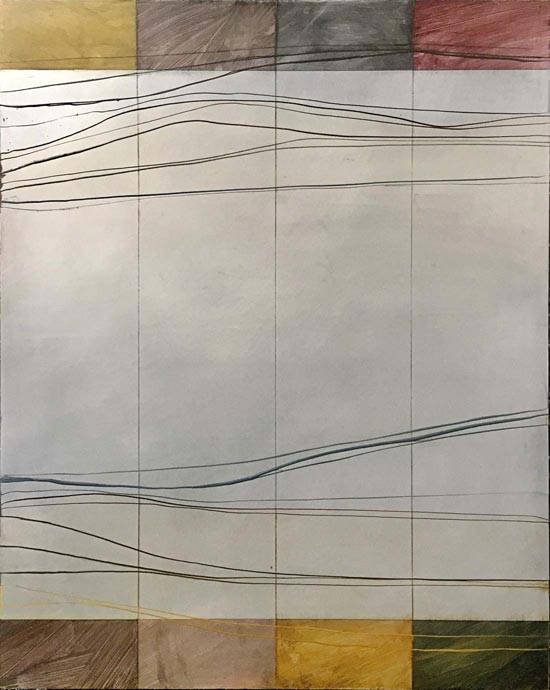

Then came the Great Famine Memorial, after one hundred and fifty years. The George Moore Society commissioned thirty-five of the country’s leading artists to engage with the theme. Many of the artists in this show, Wonderment, took part. During the summer of 1995 the big old cold cinema was stripped back to the walls and painted white to function as a gallery. I sat in the space for weeks with these enormous paintings staring me in the face. Hughie O’Donohgue’s famine figure crouched on all fours foraging; Basil Blackshaw’s blighted potatoes, Barrie Cooke’s potato ridges magnified; Michael Farrell’s skeletons and black dogs. Charlie Tyrell’s triptych, “A Spade A Spade” with its solid black cross swimming in a green plain which was hemmed in by two rectangular grey canvases bearing skeletal ribs, hung in sobriety; a metronome to steady the unbridled cacophony of artworks which jostled and simmered all over the walls.

Studio visits were a regular feature in those days. Tony O’Malley’s home was a magical place with artist, Jane O’Malley’s dream room completely in white, a big bare branch with fairy lights working as a Christmas tree in the corner. Tony’s studio was at the bottom of a garden not unlike a scene from a Monet, complete with little water-lillied pond. I was well warned not to touch anything, so I stood back in admiration of the wonderful paintings which, as they were pulled out of drawers, seemed to transport us to the tropics, magical and mystifying to me in their abstraction, their colour, and their scratched rough-hewn surfaces. Hughie O’Donoghue’s studio that afternoon in Thomastown was like an aircraft hanger which dwarfed the enormous canvases that he must have stood on a ladder to paint.

Like a lot of people I was keen to move abroad after finishing my undergraduate degree in the University of Ulster and moving into the business of art seemed a logical next step…

My parents bought a number of works by Dermot Seymour, who featured prominently in the early days of the Claremorris Open Exhibition. One of these works was a very large painting which they hung in the stairwell at home. It was impossible for me as a child to get as far as the bathroom without having to pass it. And it was with some dread that I would run past it in the middle of the night. A blondie, wind-blown woman stood in the distant sunlit arch, while in the foreground enormous pigs and a lama look out. I was amused to discover that the piece Dermot chose to include in this exhibition was that of a sow, little did he know how his painting had tormented me as a child.

Like a lot of people I was keen to move abroad after finishing my undergraduate degree in the University of Ulster and moving into the business of art seemed a logical next step which took me to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago to complete a Masters in Arts Administration. The college, being associated with the city’s most important museum, had a rich history and illustrious alumni such as Walt Disney, Orson Welles, Georgia O’Keefe and Jeff Koons. There was a strong interdisciplinary ethos and while the Institute’s reputation rested on its Painting and Drawing Department, very few students worked with paint or graphite at the time. Their efforts were conceptual, and even within the Painting and Drawing programme students cross-pollinated with new media, performance, and installation. There were a lot of young students, having honed their image making skills at second level, struggling with a transition to conceptual art. And while the quality of video exhibited in the Renaissance Society or the Museum of Contemporary Art was world class, an awful lot of cerebral, pseudo-conceptual work was produced by students who were told on induction day that they would be “broken down to be built back up again”.

It was interesting to observe the incubation of artists in art school, being somewhat at a remove from them within the arts administration hub. Interesting too was the contrast of work produced at the Art Institute at that time with the more conventional media shown at MFA shows back home, particularly in terms of the technology available to the American students. A much more heightened contrast was evident when I went to South East Asia, as part of a delegation with a representative from each department in the college. We toured Thailand, Vietnam and Laos where we visited private homes of major international collectors of contemporary Asian Art, we also called on museums and galleries. We’d seen a lot of Chinese photography and video in private collections which was graphic (not unlike Western Art in the late 1970s) but more shock-based social commentary; full of revolt.

However it was difficult to reconcile the work we’d seen by those international Asian artists with the method of teaching at the main art college in Hanoi. There a representative from each department in the Vietnamese college had to give a presentation of their work and this was then followed by a presentation from their American counterparts. The exchange was fascinating. One Vietnamese student talked us through his work, his technical abilities were outstanding, he had flawlessly reproduced Rembrandts, Picassos, a Hieronymus Bosch and bronze busts of Vietnamese communists. He had spent six years honing his technical skills but had never seemingly considered art in terms of self-expression. Then a student from our painting department showed a video of himself turning a kitchen chair into a pile of dust with an angle-grinder. The two artists were mutually mystified by the cultural chasm between them as was I.

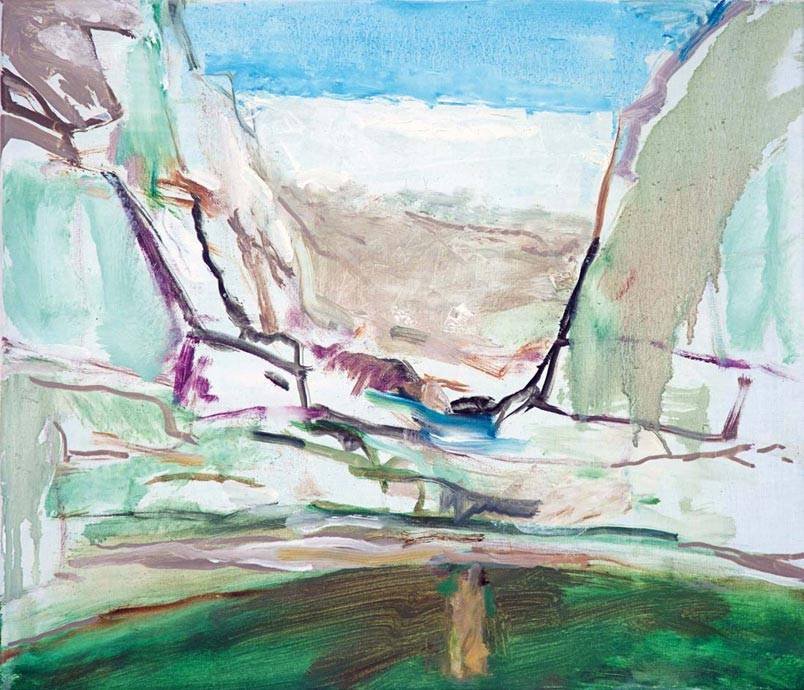

Growing up looking at art alters the way you look at the world around you. It sharpens your senses and in turn enhances your experience of the world. Brian Bourke’s fluorescent palette seemed unnatural, improbable until I flew back into Shannon after a summer abroad and watched a blaze of neon green emerge through the clouds and thought where have I seen that before. And despite seeing it every day I never noticed the distinct diffusion of sunlight in Mayo until I recognised it in Martin Gale’s painting. Painters create objects to which we relate, images to be deciphered and interpreted, but a good painting teaches us something, and a great painting moves us in some way. As with a good poem or play, a strong painting forces us to forget what we think we know and to broaden our gaze.

Like a lot of people I was keen to move abroad after finishing my undergraduate degree in the University of Ulster and moving into the business of art seemed a logical next step…

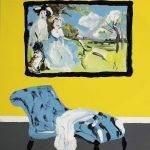

The artists invited to show in Wonderment are those who loomed large in my childhood in one way or another. A young Bernadette Kiely taught me how to properly hang a show as my sister and I helped her install in the Old Cinema building. In transition year Brian Bourke taught me how to make a copper etching. I spent a fortnight working as a housekeeper for Michael Farrell in the south of France who taught me how to weed a vegetable garden. Some were family friends. Others I did not know personally but walked by their paintings every day in my childhood home. I stuffed their exhibition invites in the car outside school in a mad rush for the post, sat in galleries minding their shows, visited their openings, studios and homes, studied their artwork at school and university.

Looking back there probably couldn’t have been a less auspicious time to open a gallery than 2007, my first big show, a great commercial success, and the last gasp of the domestic art market before a ten year recession with a string of shows without a single red dot. Over the years I have enjoyed working with dozens of artists across various disciplines and at every stage of their careers, but it’s the artists in this show and their unwavering commitment to their practice who inspired and sustained my early wonderment.

Leave a Reply